The interest of the community then is, what? – the sum of the interests of the several members who compose it. The community is a fictitious body, composed of the individual persons who are considered as constituting as it were its members. The interest of the community is one of the most general expressions that can occur in the phraseology of morals: no wonder that the meaning of it is often lost. By utility is meant that property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness, (all this in the present case comes to the same thing) or (what comes again to the same thing) to prevent the happening of mischief, pain, evil, or unhappiness to the party whose interest is considered: if that party be the community in general, then the happiness of the community: if a particular individual, then the happiness of that individual.

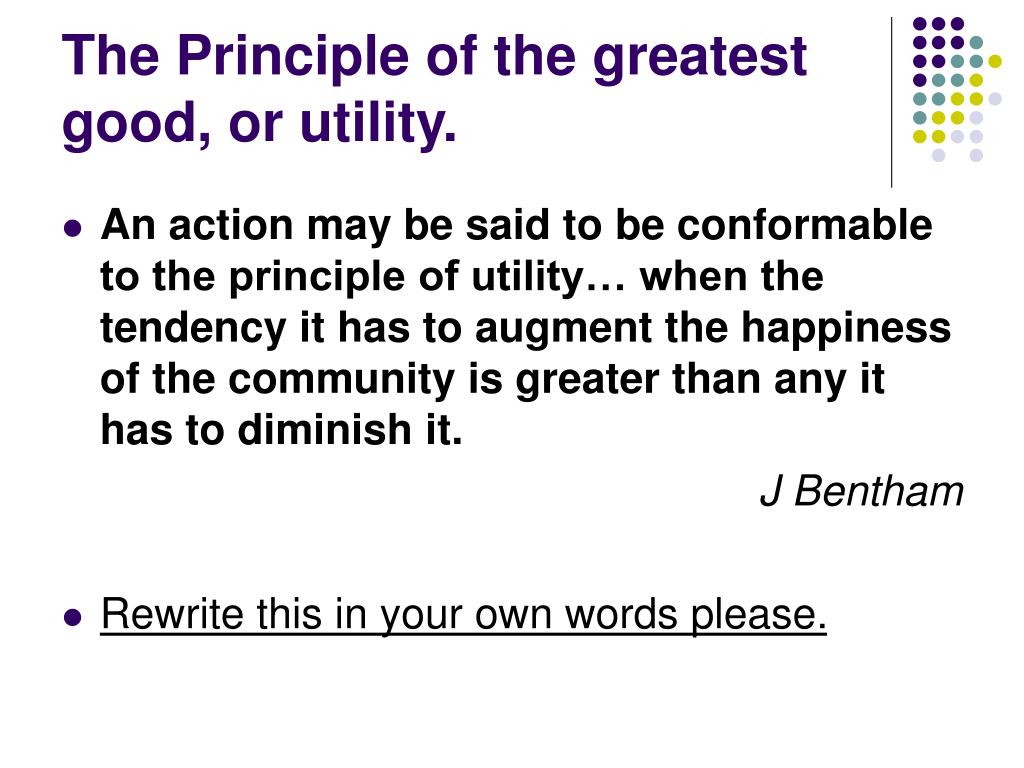

I say of every action whatsoever, and therefore not only of every action of a private individual, but of every measure of government. By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever, according to the tendency it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question: or, what is the same thing in other words, to promote or to oppose that happiness. The principle of utility is the foundation of the present work: it will be proper therefore at the outset to give an explicit and determinate account of what is meant by it. Systems which attempt to question it, deal in sounds instead of sense, in caprice instead of reason, in darkness instead of light.īut enough of metaphor and declamation: it is not by such means that moral science is to be improved. The principle of utility recognizes this subjection, and assumes it for the foundation of that system, the object of which is to rear the fabric of felicity by the hands of reason and of law. In words a man may pretend to abjure their empire: but in reality he will remain subject to it all the while.

They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think: every effort we can make to throw off our subjection, will serve but to demonstrate and confirm it. On the one hand the standard of right and wrong, on the other the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)